Understanding Anxiety: The Role of Physical Safety and the Nervous System

Anxiety is a common and often distressing experience that affects millions of people worldwide. While it is frequently thought of as a mental or emotional issue, anxiety is deeply rooted in the body—particularly in the nervous system. Our sense of physical safety, or lack thereof, plays a crucial role in how our nervous system responds to perceived threats, and this can lead to the development of chronic anxiety. Understanding this connection can be empowering, helping individuals take practical steps toward healing.

This piece explores how our nervous system influences anxiety, how our physical sense of safety can contribute to its onset, and ways to manage and reduce anxiety through nervous system regulation, lifestyle changes, and psychotherapy.

The Link Between the Nervous System and Anxiety

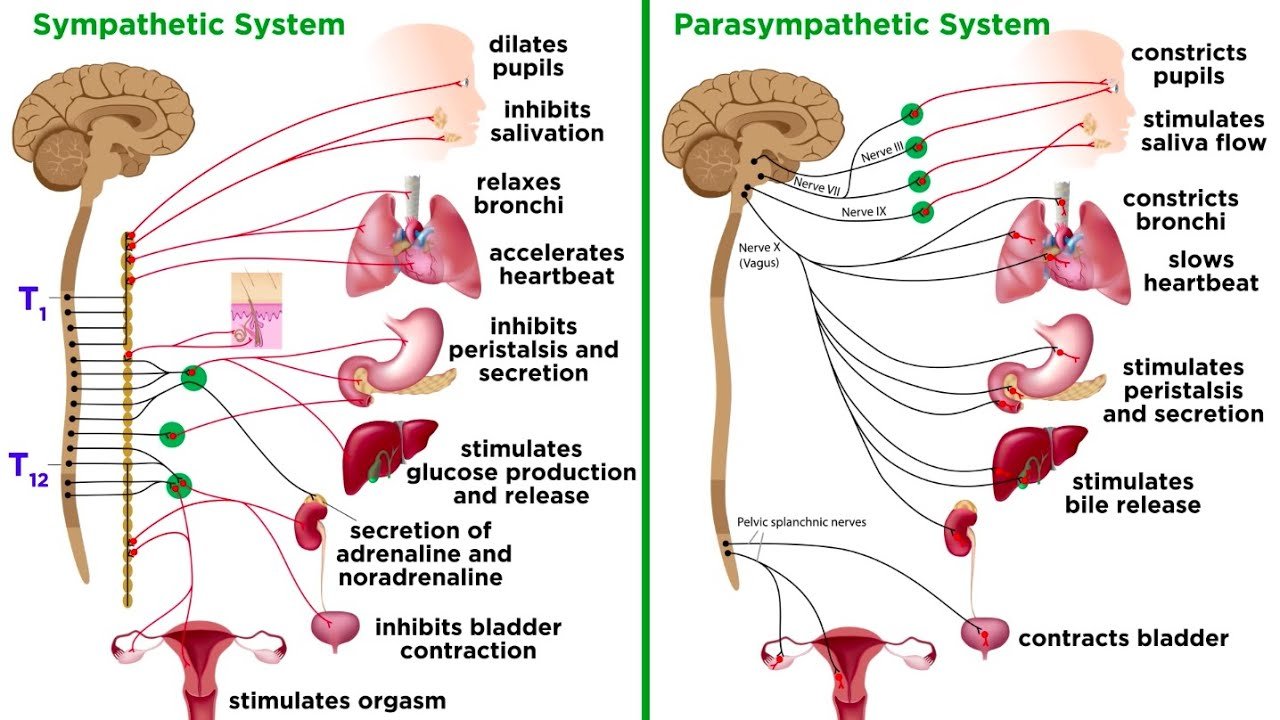

Our nervous system is responsible for how we perceive and respond to the world around us. When we experience anxiety, it is often because our nervous system is stuck in a heightened state of alertness. To understand this, it is helpful to look at the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which consists of two main branches:

• The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) – This is often referred to as the “fight-or-flight” system. It is activated when the brain perceives a threat, preparing the body to respond. Heart rate increases, breathing becomes shallow, muscles tense, and digestion slows down.

• The Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) – Known as the “rest-and-digest” system, this branch helps the body return to a state of calm after a stressor has passed. It lowers heart rate, deepens breathing, and promotes relaxation.

When the nervous system functions properly, these two branches work in balance. However, if someone experiences prolonged stress, trauma, or a persistent sense of unsafety, the SNS can remain overactive, leading to chronic anxiety (Porges, 2011).

Polyvagal Theory and Anxiety

Polyvagal Theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges (1995), provides a deeper understanding of how our nervous system responds to stress. It suggests that there is a third branch of the ANS, the social engagement system, which helps us feel connected and safe with others.

• When we feel safe, we can engage socially, think clearly, and feel calm.

• When we sense danger, we shift into fight-or-flight mode.

• If a threat feels inescapable, our nervous system may shut down, leading to feelings of dissociation, numbness, or depression.

For individuals with anxiety, their nervous system may be frequently triggered into a fight-or-flight response, even when no real danger is present. This can be due to past trauma, chronic stress, or an environment that does not feel physically or emotionally safe.

The Role of Physical Safety in Anxiety

Our sense of physical safety is a fundamental human need. When we feel unsafe, whether due to environmental factors, past experiences, or internalized fears, our nervous system remains on high alert. Some key factors that impact our sense of safety include:

1. Early Life Experiences and Attachment

Early childhood experiences play a significant role in shaping our nervous system. If a child grows up in an environment that lacks emotional or physical safety—due to neglect, abuse, or unpredictability—their nervous system may become wired for hypervigilance (Schore, 2003). As adults, they may experience chronic anxiety without fully understanding why.

2. Environmental Triggers

Our surroundings can either soothe or activate our nervous system. Factors like loud noises, clutter, unsafe living conditions, or a lack of personal space can contribute to anxiety. Conversely, environments that promote safety—such as calm lighting, predictable routines, and soothing sounds—can help regulate the nervous system.

3. Past Trauma

Experiencing trauma, whether physical or emotional, can leave lasting imprints on the nervous system. Even if the danger is no longer present, the body may continue reacting as if it is. This is why some individuals experience anxiety in situations that are objectively safe but remind them of past threats (Van der Kolk, 2014).

4. Social Safety and Connection

Human beings are wired for connection. Isolation or strained relationships can activate the nervous system’s stress response, leading to increased anxiety. Feeling seen, heard, and valued by others is essential for nervous system regulation.

The nervous system reacts to the world around us, but also to perceived stress or danger.

Ways to Address Anxiety by Regulating the Nervous System

Understanding the connection between physical safety, the nervous system, and anxiety allows us to take targeted steps toward healing. Here are some practical ways to regulate the nervous system and reduce anxiety:

Creating a Sense of Physical Safety

•Assess Your Environment – Make your living space as calming as possible. Soft lighting, comfortable furniture, and soothing sounds can help signal safety to your nervous system.

•Establish Routines – Predictability helps the nervous system feel safe. Regular sleep, meals, and relaxation times can support regulation.

• Engage in Grounding Practices – Physical grounding, such as placing your feet on the floor, holding a warm drink, or using weighted blankets, can help your body feel more present and secure.

Engaging the Parasympathetic Nervous System

• Deep Breathing – Slow, deep breaths signal to the nervous system that there is no immediate danger. Techniques such as diaphragmatic breathing or the 4-7-8 method can help.

• Vagus Nerve Stimulation – Activities like humming, singing, or gargling stimulate the vagus nerve, promoting relaxation (Porges, 2011).

• Gentle Movement – Yoga, stretching, and walking can help shift the body out of fight-or-flight mode.

Strengthening Social Safety and Connection

• Seek Supportive Relationships – Being around safe, supportive people can calm the nervous system.

• Practice Co-Regulation – Engaging in calming activities with others, such as eye contact, physical touch, or synchronized breathing, can promote nervous system balance.

Physical touch can help regulate our nervous systems

How Psychotherapy Can Help

Psychotherapy provides a safe space to explore anxiety, understand its roots, and develop tools for nervous system regulation. Some therapeutic approaches that can be particularly helpful include:

1. Somatic Therapy

Somatic therapies, such as Sensorimotor Psychotherapy or Somatic Experiencing, focus on releasing stored trauma from the body and helping individuals develop a greater sense of physical safety (Levine, 1997).

2. Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

CBT helps individuals identify and change unhelpful thought patterns that contribute to anxiety. By reframing fears and building new coping strategies, CBT can support nervous system regulation (Beck, 2011).

3. Polyvagal-Informed Therapy

Therapists trained in Polyvagal Theory help clients work with their nervous system responses, teaching strategies to shift from fight-or-flight into a state of safety and connection (Dana, 2018).

4. EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing)

For those with trauma-related anxiety, EMDR helps process distressing memories, reducing their emotional intensity and allowing the nervous system to return to balance (Shapiro, 2018).

Summary

Anxiety is not just a mental or emotional issue—it is deeply connected to the body and the nervous system. Our physical sense of safety plays a crucial role in how our nervous system responds to the world, and when we lack this sense of safety, anxiety can become chronic. However, by understanding these connections, we can take proactive steps toward healing.

Whether through environmental changes, nervous system regulation techniques, or psychotherapy, it is possible to move from a state of hypervigilance to one of safety and calm. If you or someone you know struggles with anxiety, consider seeking support from a therapist who can help navigate the journey toward nervous system healing and emotional well-being.

References

• Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. Guilford Press.

• Dana, D. (2018). The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

• Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. North Atlantic Books.

• Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301-318.

• Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

• Schore, A. N. (2003). Affect Regulation and the Repair of the Self. W.W. Norton & Company.

• Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy, Third Edition: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. Guilford Press.

• Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.